This blog post will show you how a step by step transition from a „java 7 and j.u.c.Future“ based implementation to an „akka actor written in scala solution“ looks like. It will take four steps, which are

- Java 7 and futures

- Java 8 and parallel streams

- Scala and futures

- Scala and actors with the ask pattern

- Scala and actors (almost) without the ask pattern

The complete code repository can be found on github.

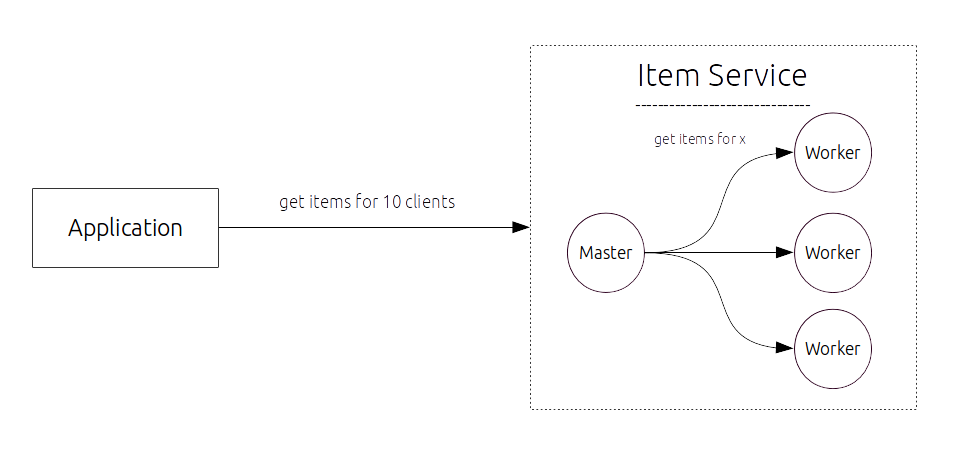

The application

The application is simple ItemService which allows you got get all the Items a client, identified by an integer id, owns. The goal is to build some statistics over the different items:

- How many clients have items with price x

- How many items have price price x

The ItemService connects (in theory) to a database, which takes a bit longer to load the data, so we don’t get the data sequentially, but concurrently. In the end we gather the results and calculate our statistics.

To see a bit what’s going on the ItemService prints out the current threadname after he finishes the getItems(clientId) call.

Java 7 and futures

The first implementation uses j.u.c.Future and some functional sugar provided by google guava’s ListenableFutures. First thing to do is to implement a Callable

public static class ItemLoader implements Callable { private final int clientId; public ItemLoader(int clientId) { this.clientId = clientId; } @Override public List call() throws Exception { ItemService service = new ItemService(); return service.getItems(clientId); } |

Nothing fancy. An ItemLoader is like a job which get’s configured via its constructor (for what client should I load items) and then instantiates an ItemService and gets the items.

Now create an ExecutorService and submit the jobs (ItemLoader instances).

List<Integer> clients = ...; // I tried some different ExecutorServices just for fun (and later some benchmarks, hopefully) int parallelism = 4; ListeningExecutorService pool = MoreExecutors.listeningDecorator(Executors.newWorkStealingPool(parallelism)); // Submit all the futures List<ListenableFuture<List>> itemFutures = new ArrayList<>(); for (Integer client : clients) { ListenableFuture<List> future = pool.submit(new ItemLoader(client)); itemFutures.add(future); } |

The MoreExecutors.listeningDecorator(..) call is from guava which decorates our initial ExecutorService. This allows us to use a very neat transition from „List of Futures with type Item“ to a „Future of List with Type Item“.

// Futures == com.google.common.util.concurrent.Futures // convert list of futures to future of results ListenableFuture<List<List>> resultFuture = Futures.allAsList(itemFutures); // blocking until finished - we only wait for a single Future to complete List<List> itemResults = resultFuture.get(); |

You may notice that we have a list of list. That’s because the ItemService returns a list of items. Lucky google guava helps us out once more with Iterables.concat, which is mostly called flatten in functional languages. This operation flattens a list of lists of type A to a list of type A.

Iterable items = Iterables.concat(itemResults); |

From here on you can do what ever you want with the list of items.

| Pro | Contra |

|---|---|

| Easy implementation | No failure handling (what job failed?) |

| Easy configuration of parallelism (ExecutorService) | blocking |

| verbose |

Java 8 Streams

Next, we will use the new awesome java 8 feature parallel streams. The usage feels a lot like the scala parallel collections and that’s why I only take a look (at the moment) at the java 8 feature as we have even more tools for concurrent/parallel programming in scala.

Talk is cheap, show me the code:

List clients = ...; // create a parallel stream from the list of clients and map each of them to a ItemService call Stream<List> serviceResults = clients.parallelStream() .map(client -> new ItemService().getItems(client)); // flatten a stream of lists of type Item to a steam of type Item Stream items = serviceResults.flatMap(itemList -> itemList.stream()); |

IMHO the syntax for flattening a stream looks a bit odd to me, but it’s the way to go. However this is the code!

| Pro | Contra |

|---|---|

| Short and expressive implementation | No failure handling (what job failed?) |

| blocking | |

| Hard to configure parallelism |

Scala and Futures

Now we move into the Scala universe. As I mentioned above, I will skip the scala parallel collections as they are pretty similiar to the parallel streams in java 8. Actually the future based implementation is pretty similar, too, but I think it’s a better start into the scala concurrency world.

First we need an ExecutionContext, which is similar to the ExecutorService. In fact you can create ExecutionContexts from ExecutorServices. For this small application we use the standard fork-join-pool.

import scala.concurrent.ExecutionContext.Implicits.global import scala.concurrent.{ Await, Future } import scala.concurrent.duration._ |

Now we can create Futures directly inside the code.

val clients = 1 until 10 toSeq // start the futures val itemFutures: Seq[Future[Seq[Item]]] = clients map { client => Future { new ItemService getItems client } } |

I wrote out the explicit types so you can see what happens here. Everything inside the Future declaration body will be executed inside an new, anonymous future. Now we transform the again the list of futures to a future of list. Scala brings this out-of-the-box.

// convert list of futures to future of results val resultFuture: Future[Seq[Seq[Item]]] = Future sequence itemFutures |

The next step is the most important one you should take away from this implementation, because until now there was no real difference to the java 7 implementation. In scala you can call map on a future, which returns a new future that has the result value mapped according to your map function. This helps you write non-blocking and readable code, because

- you don’t have to write the complete logic into one future, instead you can break it up into different methods. You can also a different result futures based on a single loading future

- you don’t have to wait for the results to transform them

A lot of talk for one line of code. We flatten the list of lists.

// flatten the result val itemsFuture: Future[Seq[Item]] = resultFuture map (_.flatten) |

After all we have to wait in this example for the results to be available.

// blocking until all futures are finished, but wait at most 10 seconds val items = Await.result(itemsFuture, 10 seconds) |

If you don’t need to wait and can handle the result at some point in time take a look at the callback functions described in the documentation of scala futures. These provide the possibility to react on failure. For futures and timeouts you can read another blog post here.

| Pro | Contra |

|---|---|

| Short and expressive implementation | Failure handling only in callbacks |

| Can be made non-blocking | if blocking you have to define a lot of timeouts |

Scala and actors with the ask pattern

All of the solutions above are valid if don’t care about error handling and fault tolerance. This can be okay in some cases, but it’s not much effort to have these too 🙂 And that’s were actors come in. If you have no idea what actors are scroll through these slides from Jonas Bonér the creator of akka, which should give you enough inside.

The first implementation will use the ask pattern, which generates futures from messages you sent. This is often need at the boundarys of an actor system to the non-actor-based part of your code. In general I made the experience to move this boundary towards „doing everything possible inside the actor system“. You’ll get the most out of akka this way.

Let’s take a look at our actor implementation

package actors import akka.actor.Actor import services.scala.{ Item, ItemService } import ItemServiceActor._ class ItemServiceActor extends ItemService with Actor { def receive = { case GetItems(client) => sender ! getItems(client) // async answer } } /** Message API */ object ItemServiceActor { case class GetItems(client: Int) } |

Bascially it wraps our existing service into an actor. You may have questioned yourself why I instantiated always a new service when calling it. Well, the service itself was not thread-safe in anyway. However now as a service is represented by an actor it is automatically thread-safe, because and actor guarantees to only process one message at a time (which in this case means method call to getItems()).

Now we do the plumbing and ask the ItemServiceActor for a list of items.

// Create the actor system which manages all the actors val system = ActorSystem() val itemService = system.actorOf(Props[ItemServiceActor], "itemService") // available clients val clients = 1 until 10 toSeq // how long until the ask times out implicit val timeout = Timeout(10 seconds) // start the futures val itemFutures: Seq[Future[Seq[Item]]] = clients map { client => // this is the ask: itemService ? GetItems(client) (itemService ? GetItems(client)).mapTo[Seq[Item]] } |

The code is almost self-explanatory, expect the mapTo[Seq[Item]]. At the moment akka raw actor implementation doesn’t provide any typesafty for the messages. So an ask will always return a future with type Any, which then is mapped to the specific type you want with the mapTo call. The rest of the code is similar to the scala and futures code.

But what about error handling? The ask pattern provides a bit more functionality then the normal futures. In a follow blog post I will show you how to handle a flaky ItemService. In short you can do this

val future = akka.pattern.ask(actor, msg1) recover { case e: ArithmeticException => 0 } |

| Pro | Contra |

|---|---|

| Threadsafe service (less instances needed) | ask timeout-hell |

Scala and actors (almost) without the ask pattern

As I mentioned in the last chapter, moving the boundary towards doing everything inside the actor system is a good thing, we will do this. By doing so we will also get a glimpse on the different and powerful error handling strategies of akka (or the actor model itself).

This implementation needs a bit more on the message api side, so we start here.

/** * Defining the aggregation API */ object ItemServiceAggregator { // ---- PUBLIC ---- case class GetItemStatistics(clients: Seq[Int]) case class ItemStatistics(results: Seq[(Int, Seq[Item])]) // ---- INTERNAL ---- private[actors] case class GetItems(client: Int, job: Long) private[actors] case class Items(client: Int, items: Seq[Item], job: Long) private[actors] case class Job(id: Long, source: ActorRef, clients: Seq[Int], results: Seq[(Int, Seq[Item])] = Seq.empty) { def isFinished(): Boolean = results.size == clients.size } /** Worker actor similar to ask pattern ServiceActor */ class ItemServiceActor extends ItemService with Actor { def receive = { case GetItems(client, job) => sender ! Items(client, getItems(client), job) // async answer } } } |

The main difference are

- A result case class ItemStatistics which holds a sequence with (client, items)

- A case class Job which encapsulates the state of a GetItemStatistics request

- The actual ItemServiceActor is almost identical, but with preserving the job id

Now to the actual ItemServiceAggregator which starts a job and distributes the work to the ItemServiceActors.

package actors import akka.actor._ import akka.routing.RoundRobinPool import scala.collection.mutable.{ Map => MutableMap } import services.scala.ItemService import services.scala.Item import ItemServiceAggregator._ class ItemServiceAggregator extends Actor with ActorLogging { // Create a pool of actors with RoundRobin routing algorithm val worker = context.system.actorOf( props = Props[ItemServiceAggregator.ItemServiceActor].withRouter(RoundRobinPool(10)), name = "itemService" ) /** aggregation map: (request, sender) -> (client, items) */ val jobs = MutableMap[Long, Job]() // A VERY basic jobId algorithm var jobId = 0L def receive = { case GetItemStatistics(clients) => jobId += 1 jobs(jobId) = Job(jobId, sender(), clients) log info s"Statistics for job [$jobId]" // start querying clients foreach (worker ! GetItems(_, jobId)) // Get results from a job case Items(client, items, jobId) => val lastJobState = jobs(jobId) val newJobState = lastJobState.copy( results = lastJobState.results :+ (client, items) ) if (newJobState isFinished ()) { // send results and remove job newJobState.source ! ItemStatistics(newJobState.results) jobs remove jobId } else { // update job state jobs(jobId) = newJobState } } } |

The logic of the aggregator is based on a few steps

- Receive a GetItemStatistics(clients) message.

- Start a new job by increment the jobId counter and store the job state in a mutable map

- Receive the Items results as message.

- If all clients have been requested, send the results, else just aggregate the results

Based on this scheme you can easily add more error handling as needed. For a per-job-error-handling one can create a JobActor for each job, which calls setReceiveTimeout, which sends the actor a ReceiveTimeout message, when being idle for too long.

Summary

First of all, use the implementation that suits your needs! If you don’t need a full-blown error handling or fine grained dispatching logic, go for the easy ones first. Scala futures are really simple and powerful. If you like more syntactic sugar take a look at SIP-22 – Async, which helps you writing less code, while using futures.

Starting easy also works if you application grows more than you initially expected. Using Scala futures makes it easy to switch to actors as you can easily extract the logic into actors and using the ask pattern to get the same future. Then you can refactor the actor inside step by step as needed.

The code can be found on Github